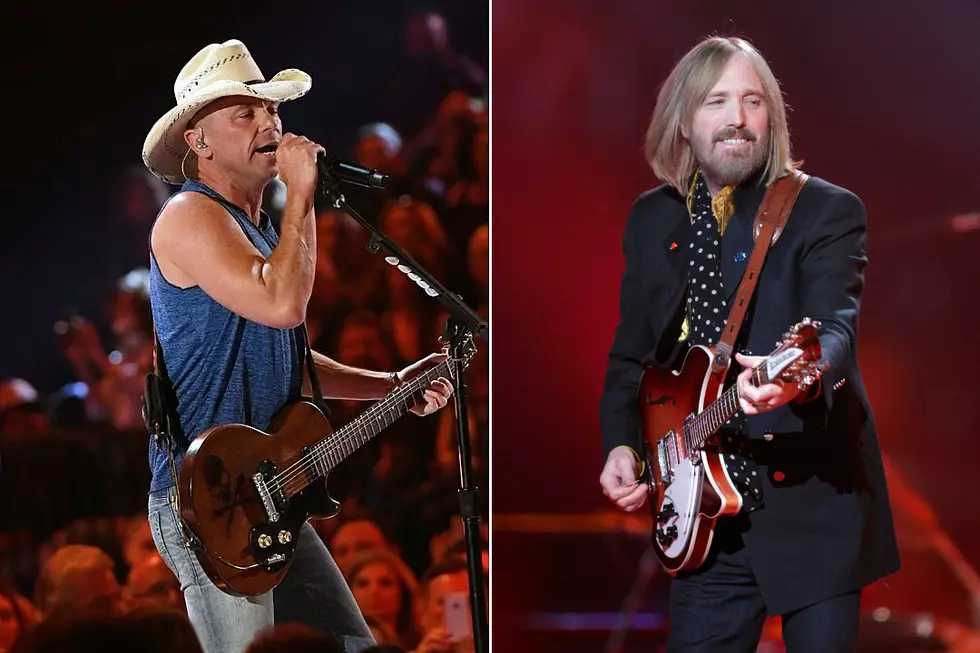

How Kenny Chesney’s ‘Everyone She Knows’ Echoes the Spirit of Tom Petty’s ‘American Girl’

The following is a personal essay from The Boot contributor Natalli Amato.

Since Kenny Chesney released his latest radio single “Everyone She Knows” in February, the song has spent seventeen weeks (and counting) on Billboard’s Country Airplay chart. It's an impressive, albeit not very surprising accomplishment for a man who has taken 60 hit tracks into the Top 10 on that very same chart.

Once "Everyone She Knows" reached the airwaves in my own hometown, I got an urgent text from my mom: “The new Kenny Chesney song is so you. Go listen.”

My mom and I share country songs with each other all the time. But it isn't typical that those exchanges are prefaced with the words “It’s so you,” elevated with the excitement of hearing our unique spirit and humanity in the lyrics. I reckon we are not special in this regard. There are a lot of women in this world, after all.

I am someone who listens to my mother, so I played the song immediately. “Everyone she knows is getting married / All the girls who used to get around / Cut their hair up to their shoulders / Spend all their Sunday’s sober now.” Had Chesney logged into my Instagram? Seen the infinite scroll of my cleaned-up sorority sisters, my childhood friends with children now themselves? Seen me, still posting boat and concert pics, a Miller Lite in a ring-less hand?

I sent the song to my best friend, Lena. “This is so us: ‘She's bored with all the boys / The men are too damn old.’”

Shane McAnally, Ross Copperman and Josh Osborne are the writers behind those lyrics. While I do not know these men personally, I can venture from these songs that they are the kind of men who pay close attention to the complicated dimensions of women’s lives.

Given that the most recent study of gender representation and country music found that women country artists only make up 10% of the airplay, one can’t realistically expect to tune into their local country music station to hear about the lives of modern women. So when men tell our stories with grace and care – as Chesney does – it matters. It helps change the norms that are set in the minds of listeners. When country fans hear artists describe women as explorers, thinkers, and adventurers instead of just blue jean shorts-shakers and silent shotgun-riders, it allows a more welcoming space for women to share experiences and stories through their own music. This is the first step in making more room at that figurative, often talked-about table.

Chesney knows what he’s up to. In 2014, ahead of the release of his album, The Big Revival, he told Billboard: “Over the last several years, it seems like anytime anybody sings about a woman, she’s in cutoff jeans, drinking and on a tailgate — they objectify the hell out of them. Twenty years ago, I might have written a song like that — I probably did. But I’m at a point where I want to say something different about women.”

Chesney is being humble here. (Or maybe he knows he can't fully escape "She Thinks My Tractor's Sexy.") Twenty years ago, though, he released No Shoes, No Shirt, No Problems. This album was the birthplace of many of his now-classic songs including, “Big Star,” “The Good Stuff,” and “On the Coast of Somewhere Beautiful.” I was five years old when that album came out. My mother played those songs for me. We loved those girls in those songs. We knew them. There’s a line in “Big Star” that captures this perfectly: “The young girls scream out loud / Man, that could be us.”

I’ve been screaming that feeling out along to Kenny Chesney songs my whole life.

Chesney once told ET, “I’m learning that when you write songs about women, the perfect place to start is their spirit.” Over the past 20 years, he's made a career built on songs that do this: “The Woman With You,” “There Goes My Life” “Somewhere With You,” “Happy on the Hey Now (A Song for Kristi),” “Wild Child, “Boston,” “All the Pretty Girls.” (And I could go on.)

What are the women in these songs doing? They’re closing business deals. They’re leaving everything they know and heading to the coast. They’re fighting with their moms and looking for a getaway. They are our dear, dead friends we desperately want to see once again. They’re headed to Bonnaroo. They put school and family on hold to find out who they really are, one newly-discovered reggae track at a time. They want you to get ready to pick them up at eight.

These are women I know. These are women I have been. And Chesney is right – the recognition here is happening in the realm of spirit. It’s what makes “Everyone She Knows” feel like looking into the bathroom mirror and charting peers like “One of Them Girls” feel like peering into a looking glass at a funhouse.

These are the songs that fill NFL stadiums every summer. Because people, no matter their gender, respond to things that possess beauty, truth and goodness. Writing in cliches and stereotypes most often bypasses these sacred traits.

Chesney's discography did not invent this care for complex women characters in the hands of men. It is part of a legacy – as all music is. That legacy starts at the Shelter Studio in Hollywood, Calif. in 1976 with a band from Gainesville, Florida. It starts with Thomas Earle Petty and the last track on The Heartbreakers' debut album -- the track that would become a touchstone of American culture, a myth-maker and an archetype, and one of the greatest songs of all time: “American Girl.”

“Well, she was an American girl / Raised on promises / She couldn't help thinkin' / That there was a little more to life somewhere else.”

When I hear this opening line and the signature riff that precedes it, I think, this sounds like what dreaming feels like. What yearning feels like. This sounds like girlhood.

When Petty sings, “After all it was a great big world / With lots of places to run to / And if she had to die tryin' / She had one little promise she was gonna keep,” I know this world. It’s the same world that “Everyone She Knows” exists in. It is the real world but dipped in music. Which is to say it is the real world dipped in magic.

You can hear Petty’s love for his character in his song. He once told Rolling Stone, “The American Girl is just one example of this character that I write about a lot. The small-town kid who knows there’s something more out there, but gets fucked up trying to find it. I always felt sympathetic with her.”

She shows up everywhere in Petty’s universe. She teaches Eddie to play guitar on “Into the Great Wide Open.” Some guy is trying to woo her with money and drugs, but she listens to her compass in “Listen to Her Heart.” She is her own protector on “Time to Move On.” She’s a poet and a forgiver on “Leave Virginia Alone.” She visits Chesney on "Everyone She Knows."

In 2013, Petty shared his thoughts on modern country music. "I mean, I hate to generalize on a whole genre of music, but it does seem to be missing that magic element that it used to have," he explained. "I’m sure there are people playing country that are doing it well, but they’re just not getting the attention that the shittier stuff gets. But that’s the way it always is, isn’t it?"

I cannot say what Petty’s definition of “that magic element” was. I can only try to talk about what it means to me.

Recently, I found myself out on the lake with some of the boys I grew up with. When I say “grew up with,” I mean the boys we snuck out screen doors to drink warm beers and listen to Chesney songs around bonfires with. Back then, it was “Come Over” and “You and Tequilla” on repeat. Once again, we had Chesney playing loud, one more old friend joining us in that boat. This time, “Here and Now” and “Everyone She Knows” are on the speakers.

Chesney plays while we talk. Spencer pulls up a picture of the Heartbreakers' logo. He says it will be his next tattoo. I turn to show him the wildflowers that have been on my back since Oct. 3, 2017, the day after Petty died. For myself and countless other country fans, these moments define "the magic element."

PICTURES: See Inside Kenny Chesney's Spectacular $14 Million Tennessee Estate

More From KEAN 105

![Lizanne Knott, Jesse Terry and Michael Logen, ‘Learning to Fly’ [Exclusive Premiere]](http://townsquare.media/site/623/files/2018/11/Lizanne_-Jesse_-Michael-Photo.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![Chris Stapleton, Emmylou Harris Honor Tom Petty With ‘Wildflowers’ at 2018 Grammys [WATCH]](http://townsquare.media/site/623/files/2018/01/chris-stapleton-emmylou-harris-2018-grammys1.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![American Aquarium Remember Tom Petty With ‘Listen to Her Heart’ [WATCH]](http://townsquare.media/site/623/files/2017/10/american-aquarium-tom-petty-cover.png?w=980&q=75)

![Jason Isbell Offers Tom Petty Tributes in Memphis, Nashville [WATCH]](http://townsquare.media/site/623/files/2017/10/Jason-Isbell.jpg?w=980&q=75)